GitHub repository: [link]

Reference paper: Physiologically Inspired Blinking Behavior for a Humanoid Robot [PDF] [BIB]

Authors: Hagen Lehmann, Alessandro Roncone, Ugo Pattacini, and Giorgio Metta

Submission: 2016 International Conference on Social Robotics (ICSR16), Kansas City, MO, U.S.A., November 1-3

Blinking behavior is an important part of human nonverbal communication. It signals the psychological state of the social partner. In this study, we implemented different blinking behaviors for a humanoid robot with pronounced physical eyes. The blinking patterns implemented were either statistical or based on human physiological data. We investigated in an online study the influence of the different behaviors on the perception of the robot by human users with the help of the Godspeed questionnaire [Bartneck2009]. Our results showed that, in the condition with human-like blinking behavior, the robot was perceived as being more intelligent compared to not blinking or statistical blinking. This finding represents the starting point for the design of a ‘holistic’ social robotic behavior.

Method

We used human social behavior data to model social behaviors for the robot, and then to test these behaviors in Human-Robot Interaction contexts. We used both an optimization approach for the behaviors on the robot and a synthetic modeling approach for the testing of these behaviors in natural environments.

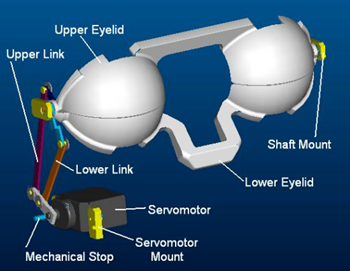

iCub Eyelid Mechanism

For the implementation and testing of our blinking module we used the iCub robot. It has very pronounced eyes resembling human features like a black pupil, white sclera, and moveable upper and lower eyelids (see introductory Figure).

human-like Blinking

For the human-like blinking behavior, we chose to use as a starting point the physiological data provided by [Doughty2001] and to adapt it to technical limitations of the iCub eyelid mechanism. The general settings for the conversational blinking module are an average blinking rate of 23.3 blinks per minute with an inter eye blink interval of 2.3 +/- 2.0 s. The blinks of the robot are in 85% of the cases single blinks and in 15% of the cases double blinks.

We divided each blink into three phases, the attack phase when the eye is closing, the sustain phase when the eye is closed, and the decay phase when the eye is opening again. The attack phase has an average length of 111ms with a standard deviation of 31ms. The sustain phase lasts on average 20ms with a standard deviation of 5ms. The average length of the decay phase is 300ms with a standard deviation of 123ms. The robot also blinks on each onset and offset of its verbalizations.

The adaptation of the original physiological data from Doughty became necessary due to the specifics of the iCub eyelids. Unlike in a human eye, the robots upper and lower eyelids move the same way during the blink. When using the original human data, this results in a much faster closure of the eye (the eyelids meet in the middle of the eyeball). This resulted in what was described by participants in a short pilot study as ‘hectic blinking’. By adapting the different speeds of each of the phases it was possible to give the movement a more human-like appearance.

Experimental Setup

In order to evaluate influence of the blinking behavior on the impression the robot has on participants we generated three conditions with different blinking patterns. For the robot to appear to be in a social interaction during the experiment, we scripted a one-interview. In order to make this interview interesting and informative for the participants watching it, we decided to “discuss” with the robot a game it plays usually during demonstrations and exhibitions. The questions asked in this interview and the robots answers were the same in each of the three experimental conditions.

- Condition 1: The robot looked straight ahead without blinking while answering the questions of the experimenter.

- Condition 2: The robot blinked every

5seconds using the timings for the attack, sustain, and decay phases described in human-like blinking. It performed no double blinks. - Condition 3: The robot blinked with a rate of

23.3blinks per minute. It performed double blinks and blinked at the onset and offset of its verbalizations. The timing was of the three phases of the blink were as described in human-like blinking.

We used the Godspeed Questionnaire [Bartneck2009] to evaluate the impression a person has of a robot on five different subscales. These subscales are anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability, perceived intelligence, and perceived safety. Since we hypothesize that the blinking behavior will improve the user experience with the robot, we expected that in condition 3 the robot would score higher compared to condition 1 and condition 2 in anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability and perceived intelligence.

Discussion

Our results show that the robot, when displaying human-like blinking, was perceived as being more intelligent according to the categories of the Godspeed questionnaire [Bartneck2009]. For its other subscales, no significant differences were found. This illustrates that even though human-like blinking behavior can make a significant difference in how humans perceive robots, it is only one aspect of human nonverbal communication that needs to be taken in consideration when designing social behaviors for robots. Naturalistic blinking in itself it is not enough for a robot to meet the requirements for its social integration, such as for example perceived safety, likeability, and animacy. We could think to blinking as an important, but not a sufficient characteristic regarding social integration.

Being perceived as intelligent can be advantageous for the effectiveness of a robot specifically in situations in which it has to transmit information in a social context, e.g. when the robot is used as a guide or informant in shopping malls, train stations or in tourist information centers. A robot that is perceived more intelligent is likely to be considered more competent and trustworthy in these cases.

The result that the naturalistic blinking behavior was more appreciated by users indicates that the synthetic methodology – i.e., modeling natural behaviors in artificial (in our case robotic) systems [Damiano2011] – is a promising way to create successful applications for HRI. In other words, this methodology appears able to allow us to build better social robots, i.e. robots with a more convincing social presence, as well as to test psychological and sociological paradigms about their integration in human societies.